8.07.2019

My favourite thing about owning a car from 1981 is that there are more ashtrays seats, more ashtrays than there can feasibly be people; there’s one in each backseat door, one behind the central console, one beside the steering wheel, one above the radio, and one in the glovebox.

Six.

Six ashtrays.

I don’t even smoke. This delights me.

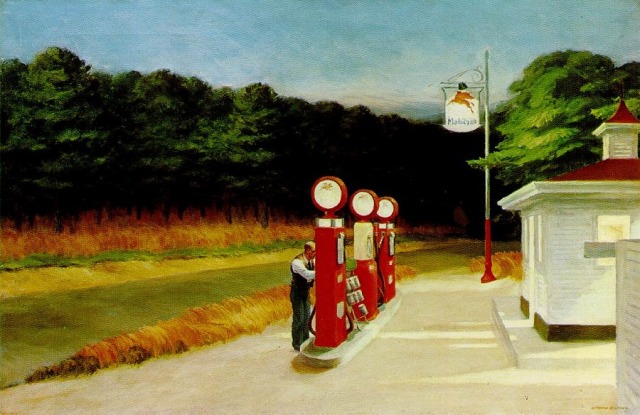

My least favourite thing about owning a car from 1981 is that there are no drink holders. Dad tells me that this is because the car was made before drive-thru was invented. Up until this point, I hadn’t even thought about the fact that drive thru was one of those things that had needed to be invented, that it was something someone had thought up, had gone from not existing to existing and altering the design of vehicle interiors. I tell myself there’s a documentary about this somewhere, but I don’t try to watch it.

Instead I spill my coffee every single morning.

And I understand that if I’d gotten a Subaru from 2012 this wouldn’t have happened. If I’d gotten a Subaru from 2012 I’d have a clean shirt, cup holders, and a sensible fuel economy. If I’d gotten a Hyundai from 2009 I would be able to keep up with other cars on the highway, presumably the windows would seal when you closed them, perhaps the heating might work, you might be able to come to a stop from a high speed without downshifting lest she stall altogether for some goddamn reason.

But I have a Toyota Corona from 1981 and she is the most beautiful thing that I own.

I bought her for that reason and that reason alone, there’s nothing more to it than that.

She’s the only vehicle I’ve ever bought that already had a name, Levendi. Handsome. My handsome girl. I introduce her as Madame Old as Fuck. But she gets me to work, and she gets me back, and I am thankful for that, hurtling along with all the other drivers, learning how to commute, something I’ve never done before. Learning that there are rhythms, etiquettes, generosities and discourtesies both operating in the same space, bouncing up against each other in occasionally deadly ways and I’m fascinated by it.

I am fascinated by the fact that the ideal of all the drivers around me is that there are no other drivers, all of them wishing for the roads to be clear, the police officers absent, and the highways barren. I imagine it like being in a swarm of locusts, if locusts hated being in a swarm. We think about each other like we think about weather systems, cold fronts, rain clouds, thunderstorms, unfortunate coincidences, unstoppable and unavoidable, just another thing to muscle through, grumbling as we go.

Modern life is ridiculous.

But I face it in my ancient car, creaking along the motorway, my matchbox of a vehicle pushing off death for another day in her thirty eight year career. And I work hard on not grumbling, on making certain that I don’t grumble.

I love my car.

…

17.08.2019

I crashed my car.

…

I remember the way it happened in episodes, snapshots.

I remember that I was listening to Gillian Welch, I remember that the rain had been coming down for a day already and would continue for two more. I remember that I was mad at my boss, furious, I remember noting the puddle but thinking nothing of it, I remember the corner, I remember the terror that had roared up through my chest, the half seconds, the empty belly sudden lack of traction, driving on vaseline, the terror again. The wheels slipped out from under me and I felt physics take ahold, the laws of motion taking something from me, no longer in control. I tried to turn the wheel like someone trying to break thick glass with just their fists, an empty threat, screaming with a hoarse voice at something too far away to hear, desperately trying to have an impact on universal forces, on ancient procedure, having occurred a thousand different ways on a thousand different rainy days since we’d started using hunks of metal as means of transportation.

I had provided the ingredients, but I didn’t get to say how the cake got baked.

When I crashed Levendi, my handsome girl, I went over two lanes of traffic and collided hard with the central island.

I went over two lanes of traffic and got half way into another before my momentum stopped, lodged on top of raised concrete, but in the end, it was just Levendi, just my handsome girl, the only fatality, her axles broken, her tires blown, her throttle stuck and done for. And I wailed, wailed for the fear that had wrapped itself around my lungs, for the adrenaline pumping through me, for the fact that I’d been thinking myself thirty, but I was suddenly only eighteen and so devastatingly young. I didn’t know what to do, I didn’t know who to call, couldn’t remember what road we were on, there in the rain, Gillian Welch singing sweetly in the background, undisturbed while I tried to breath through my panic like someone drowning in molasses.

But I was seen.

I was seen like a little kid wailing is taken by the hand in the supermarket, my distress offered over the loudspeakers. I was seen like a lost dog wandering the streets is picked up and taken home. I was seen like a teenager who’s never done this before is seen, hands shaking, unsteady and shallow breathed, everyone around me somehow able to see that I had nothing, no expertise, no experience, no luck left, all of it expended on just being alive.

It’s just a car, honey, the operator told me gently when I called triple zero, just breathe, you’ll be okay.

What’s important is that you’re alright, said the man who stopped to help me, who stayed with me while we waited for the cops and I wept, a broken umbrella between us, offering me seemingly everything he had in his car, a phone, a dart, a sip of his gatorade, his company, anything he had to give, he gave.

It’s just an object, it’s just a thing, things are everywhere, said the police officer who breath tested me as I sobbed on the side of the road, gesturing to my broken car, my handsome girl all crumpled up like tinfoil, eyebrows together as he tried to convince me that there were so many cars left in the world for me to crash.

She’s a write off, miss, said the tow truck driver, as we sat in a side street with the rain piddling down around us, surveying the damage, but she’s a write off so you don’t have to be.

And I pull myself together, I can’t stop crying, but thats just cosmetic. I pull myself together.

By the following afternoon, I have Levendi’s number plates in the back seat of a Holden Astra from 2006 and about fourteen dollars to my name. Every day on the way home from work, I go past the dint I made, barely a scratch, where I crashed poor Levendi and every day I remember that it was worth it to have her, even briefly.

…

23.12.2019

It’s been months since I lost Levendi, and months since I started driving Sabrina, the Holden Astra.

She’s a good car, but she still doesn’t felt like mine, she still feels borrowed, rented, knowing that that she was temporary solution even then, a placeholder for the answer I hadn’t come up with yet, squinting at the sky, still not sure if I was going to need an umbrella or a tube of sunscreen. Even then, I think I knew that what I needed was to stall, that things were shifting, that I was shifting, from within the stiff roots of my full time job, I had restlessness in my bones. I bought Sabrina like a parent buys shoes for a toddler, fully away that given six months, she’d be outgrown, that she could fill only the present void, not the ones to come.

It’s been months since I lost Levendi and now it’s Christmas, the local mall is awash with colour, tinsel is everywhere, lights, wreaths of plastic plants that don’t grow here, elaborate impersonations of a European winter. We are wading through the shops, looking for things that might not be wanted or useful, but will at least convey a little love to those we give them to, might help them to understand that a far deal of New South Wales is burning, the rest of it likely to burn in the coming months, but there’s love here still, and it’s still important, no matter how on fire we get, no matter what catastrophe is on its way next.

Just outside of a play centre, theres a plastic basin on the floor, about the size of a walk-in wardrobe, a mosquito net hung from the ceiling above it, full of small children and hundreds and thousands of little paper squares. Snow.

It’s thrown every which way by excited hands, in this place where there hasn’t ever been snow, not for millions of years. Just outside its perimeter a little girl is clutching handfuls of it to her chest, methodically pushing it back into the container from where it’s spilled out onto the tiled floor. As she does, the other children throw it up into the air, letting it fall around them, kicking at the piles, jumping, dancing and letting it tumble out onto the tiled floor.

The little girl huffs and continues her work.

She knows how this is supposed to work, she’s cracked the case, knows that the snow belongs inside the ring, not out of it. And she will do what she must to put the universe right, fruitless as it may be.

I think about her all the time.

…

1.01.2020

I’m sitting on a park bench beside a lagoon, watching a group of pelicans play politics with a mob of ducks, establishing and reestablishing a chain of command, over and over. The ducks have numbers but the pelicans run in gangs and are the size of small boats. It’s a hard fight to win, but they give it a go every now and again and I can admire that. The gulls stay out of it.

And I am here, beside them, trying to figure out how to unstick my feet from the ground, one toe at a time. I’ve seen mum do this a thousand times before, watched her shake the roots of some startled plant, working on her hands and knees with earth under her nails, firmly planting it down in some new spot, better for it in the long run, just hoping it’ll survive the transition. I am trying to remind myself that it’s good, that it’s right, that I’ve seen this done a thousand times before, that just because a plant is established does not mean it is fully grown.

At the end of this month I’m going to be going to university in Adelaide. In Adelaide. A place, I’ve learned, is actually a pretty long way from here.

Every couple of minutes another thing I’ve failed to consider and investigate pops into my mind. Do they have pelicans in Adelaide? How the fuck am I going to be able to afford all those pens? Do you have to actually buy the textbooks? That sounds fake. What if there are pelicans but they’re like a different type? Like smaller? Maybe in Adelaide the ducks get to be in charge. Not sure how I feel about that actually.

And it’s like those half seconds, the wheels slipping out from under me, so many of these factors out of my hands, physics in action, the universe in motion.

A quiet, sensible part of my brain is whispering that this is all par for the course, that it won’t kill me to maybe chill out just a little bit, that it’s not like Adelaide is a war zone or anything, that it might actually be almost good not to be so in control all the time, that I don’t have to be, I can let that be okay. The voice reminds me that being an adult is all about letting go, that I’m nineteen and still brand new, that I’ve still got lots of growing to do, and maybe, maybe I’d feel better if I just left that chaos be for a bit, leant into the curve, loosened my grip; there’s no rush in the free-fall, I’ll have the time.

I think that might be something of a resolution for this year. I mean, now that I’m older, now that I know more, perhaps it’s time that I give a little back to the universe, perhaps it’s time that I relinquish a little control.

Let the snow pour out.

I remember the smell of coffee even though I didn’t know it was the coffee then, and I can see him making his list. I can envision the lists within the list for the vegetables and dairy, the yellow paper and his work pen; the white sheets, the morning sun, coming in during the ad breaks in the cartoons.

I remember the smell of coffee even though I didn’t know it was the coffee then, and I can see him making his list. I can envision the lists within the list for the vegetables and dairy, the yellow paper and his work pen; the white sheets, the morning sun, coming in during the ad breaks in the cartoons. They’ve got their shoulders squared like they’re ready for a fight, and they’re ready and willing to pry our email addresses from our cold dead fingers. The man who talks to me talks to me like he’s trying to sell me something. There is nothing that I can give him. There is no moral response I can give him that would make him feel satisfied parting from this conversation. He can’t sell me something I’ve already got. But we converse anyway, and each not knowing anything more than what we did already. There can be no debate.

They’ve got their shoulders squared like they’re ready for a fight, and they’re ready and willing to pry our email addresses from our cold dead fingers. The man who talks to me talks to me like he’s trying to sell me something. There is nothing that I can give him. There is no moral response I can give him that would make him feel satisfied parting from this conversation. He can’t sell me something I’ve already got. But we converse anyway, and each not knowing anything more than what we did already. There can be no debate.